Despite the efforts made over the past decades by some outstanding scholars, the interrelations between economic theory and economic history are far from harmonious. Economic theorists often continue to regard history as a mainly descriptive, «non-analytical» discipline. Economic historians are just as often dissatisfied with the formalism of theory and its inadequate attention to institutional aspects. But the point is that within the framework of these sciences, which do indeed take a largely different view of the economy, there are two areas—Chandlerian business history and standard cost theory—which definitely have a large potential for interaction.

Despite the efforts made over the past decades by some outstanding scholars, the interrelations between economic theory and economic history are far from harmonious. Economic theorists often continue to regard history as a mainly descriptive, «non-analytical» discipline. Economic historians are just as often dissatisfied with the formalism of theory and its inadequate attention to institutional aspects. But the point is that within the framework of these sciences, which do indeed take a largely different view of the economy, there are two areas—Chandlerian business history and standard cost theory—which definitely have a large potential for interaction.

The conception of the emergence and development of large enterprises, as developed by Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., and constituting the pivot of modern business history, stands out with its clear-cut logical structure and is, for that reason, literally predisposed to quantitative assessment and formalization.

In describing the competitive advantages of large enterprises, Chandler himself usually makes use of the term economy of scale and scope . In fact, one of his best-known books is entitled Scale and Scope . 1 However, his interpretation of the economy of scale and scope substantially differs from the traditional one.

In Chandler’s view, a successfully operating large enterprise may develop from a company which effects the «three interrelated sets of investments in production, distribution and management required to achieve the competitive advantages of scale, scope or both, inherent in the new and improved products and processes» . 2 In the event, central importance attaches to efficient use of the potential created in these spheres, to what Chandler calls the throughput problem . «Thus the two decisive figures in determining costs and profits were (and still are) rated capacity and throughput, or the amount actually processed within a specified time period. (The economies of scale theoretically incorporate the economies of speed, as I use that term in «The Visible Hand», because the economies of scale depend on both size—rated capacity—and speed—the intensity at which the capacity is utilized.)» 3

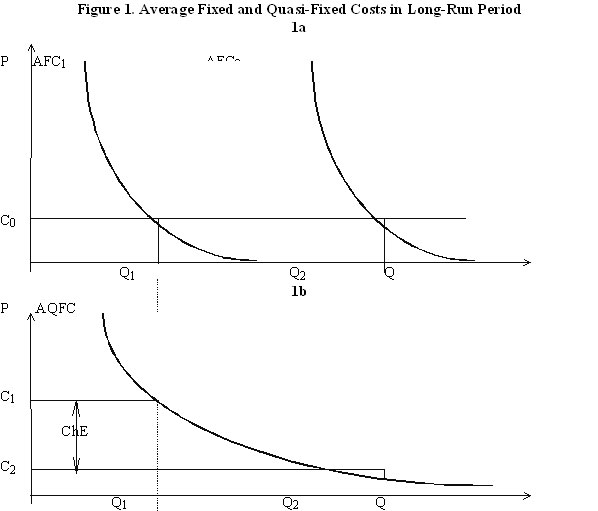

What leaps to the eye is the similarity of this logic of reasoning with the standard theoretical description of the lowering of average fixed costs as output rises in the short -run period. In actual fact, this is an essentially new theoretical approach, because Chandlerian business history is known to deal with the long-run period, in which, it is common knowledge, fixed costs do not exist at all. Indeed, in contrast to Chandler, standard theory fails to discern in the context of such a situation any sources for a reduction of average fixed costs (see Fig. 1a) and, consequently, any advantages for large firms.

It is true that in the long-run period all costs are variable. Say, a company deciding to build a new plant will be forced to rent additional land. Rental payments, which are constant in the short-run period, are inevitably bound to grow in the long-run period. The average fixed costs curve AFC 1 will shift to the AFC 2 position, and the larger output (Q 2 ) of the large company will not give it any advantage in costs as compared with the small volume of output (Q 1 ) typical of a small company. In both cases, average fixed costs will be equal to C 0 .

|

An apparent contradiction comes to the fore. Anyone who takes the trouble to make a thorough study not only of the conclusions formulated in Chandler’s works, but also of the hundreds of «biographies» of industries and individual large enterprises in many countries that make up the bulk of his works cannot help being convinced that the spread of some types of fixed costs over a vast volume of output is a historical reality, and a reality most clearly manifesting itself precisely in the long-run period. In fact, the reduction in costs per unit of output occurring as a result of this process has obviously been one of the reasons for the success of large enterprises and a prerequisite for their wide spread throughout the world.

When a pharmaceutical company spends a vast amount of money (in present-day conditions up to $500 million) to develop a new medicine or an electronic firm spends even more money to create a new microprocessor, these costs acquire an obviously fixed nature even in the long-run period: R&D costs are not liable to change depending on the amount of goods to be turned out in the future and do not even depend on whether new shops and plants are built for their production.

Investments by large enterprises in the creation first of a national and then of a world-wide distribution and marketing network (incidentally, this is one of Chandler’s favorite subjects) upon completion likewise tend to acquire a definite similarity with fixed —in the long-run period!— costs. When Procter & Gamble builds a new plant for the production of detergents, it will hardly need to go in for additional large-scale expenditures in creating a new distribution network: the corporation will make use of the one already in place. Or when Procter & Gamble , following the purchase of household chemicals plants in Russia, showers this country’s market with dozens of TV commercials earlier used in other countries, not a single additional dollar will have to be spent on their filming (as also on many other marketing devices).

Finally, an effective system of management (Chandler’s third line of investment) does not usually require, with an increase in company size, a proportional growth of costs for its maintenance in working orders: many of its elements developed in the course of a company’s successful growth (primarily corporate culture) may also be used when it attains gigantic proportions.

Incidentally, similar mechanisms of existence of fixed costs in the long-run period are also regularly noted, apart from historians, by researchers oriented towards an applied analysis of company activity. Cliff Pratten, for instance, even designated 4 as a «common sense view» the fact that «a company with a larger share of a market than its rivals for a technically sophisticated product has an important source of advantage in being able to spread research and development costs over a larger output». Similar ideas are even more frequently expressed with respect to concrete firms and industries. Thus, a publication by McKinsey & Co. says: «Once software has been developed, the marginal costs of an extra copy is negligible.» It adds, in a somewhat more general form: «A company’s ability to replicate what it has already done is a key growth accelerator.» 5

In other words, although fixed costs should apparently not exist in the long-run period, in actual fact something that looks like them is evident from the highly extensive and representative material generalized by Chandlerian business history. Actually, there is no contradiction here at all. Within the framework of standard cost theory there is an instrument for describing the uniformities discovered by Chandler. The trouble is that this instrument—the so-called quasi-fixed costs —now exists in economic theory as some kind of incidental element, a minor detail which is of interest only to pedants and is hardly known to anyone at all (apart from theorists proper).

No wonder the very term quasi-fixed cost is relatively little used. It never finds its way to the pages of the most popular introductory-level economics textbooks, while the solid course entitled «Intermediate Microeconomics. A Modern Approach» , written by Hal R. Varian and adopted as the basic course by more than 400 colleges and universities throughout the world, has room to spare on its 800 pages only for the following few lines about quasi-fixed costs:

«Fixed costs are costs associated with fixed factors: they are independent of the level of output, and, in particular, they must be paid whether or not the firm produces output. Quasi-fixed costs are costs that are also independent of the level of output, but only need to be paid if the firm produces a positive amount of output. There are no fixed costs in the long run period by definition. However, there may easily be quasi-fixed cost in the long run. If it is necessary to spend a fixed amount of money before any output at all can be produced, then quasi-fixed costs will be present.» 6

Apart from the above, Varian makes no mention of quasi-fixed costs, either in connection with the dynamics of average long-run costs or in analyzing the effectiveness of large oligopolistic enterprises, or even in the context of natural monopolies!

It is a fact that the theorist and the business historian take a different view of one and the same phenomenon. For the former, quasi-fixed costs are merely an unusual species of costs which are fixed in every case except a single one. For the latter, they are an important element in understanding the phenomenon of the modern large enterprise. The historian regards these (without, incidentally, using the actual term quasi-fixed costs ) as one of the main reasons for which large enterprises, having emerged quite recently by historical standards (100-150 years ago), have managed in this period to become dominant in the economy and clearly have no intention of giving up their position to other types of firms.

On the whole, the identification of quasi-fixed cost enables one to take a fresh look at the theory of the competitive advantages of large enterprises. As Fig. 1b shows, in virtue of the immutability of the total amount of quasi-fixed costs, an increase in producer capacity (and necessarily of actual output—let us recall the throughput problem ) from Q 1 to Q 2 brings about a reduction in average quasi-fixed cost (AQFC) from C 1 to C 2 .

It goes without saying that this gain in the level of costs is only one of the species of the economy of scale. It is, however, a special species connected with the Chandlerian three interrelated sets of investments and, accordingly, with the historical lot of large enterprises. Moreover, it is marked by an unparalleled and absolutely unique feature: it never gives way to diseconomy of scale, whatever the size of the enterprise . After all, «to replicate what is already done» truly costs almost nothing at all, however many times this procedure may be repeated.

It appears that, in view of the great importance of this type of economy of scale for the real history of large enterprises, and also for the history of the past century and a half in the development of the economy as a whole, it would be advisable to identify this type of economy by means of a special term, say, by designating it as Chandlerian economy of scale (ChE).

Simple manipulations help to establish the quantitative amount of gain in lowering average quasi-fixed cost with an increase in the size of the enterprise.

ChE = QFC/Q 1 — QFC/Q 2 = QFC(1/Q 1 — 1/Q 2 ),

where:

ChE is the Chandlerian economy of scale ,

Q i is the output of enterprises of various size,

AQFC i is the average quasi-fixed cost, and

QFC is the quasi-fixed cost.

Taking Q 2 = aQ 1 or a = Q 2 /Q 1 , we get:

ChE = QFC(1/Q 1 — 1/aQ 1 ) = (1 — 1/a)QFC/Q 1 = (1 — 1/a)AQFC 1

So, the gain in reducing average quasi-fixed costs with an increase in the size of the enterprise depends on their initial amount (AQFC 1 ) and on a certain coefficient (1 — 1/a) reflecting the scale of this increase. It is convenient to determine the latter as follows:

k ch = 1 — 1/a = 1 — Q 1 /Q 2 .

The magnitude of the Chandlerian economy of scale will then be expressed in this simple formula:

ChE = k ch AQFC 1

At any change in the size of an enterprise within the interval

1 < a < infinity,

the coefficient k ch changes within these limits:

0 < k ch < 1.

In the limiting case of an infinitely large increase in the size of an enterprise, the formula acquires the form of ChE = AQFC 1 , that is, theChandlerian economy of scale compensates the entire initial volume of average quasi-fixed cost.

Incidentally, could there be evidence of an approximation to this limiting case in the Internet , where many programmes are offered for a token fee or free of charge? The number of users of the global network is now so large that outlays on the development of software can be financed through a minimum charge or through sideline revenues (say, from placement of advertisements on the same server), that is, free of charge for the user.

It appears that the way outlined above for enhancing the interaction between Chandlerian business history and standard cost theory could yield large mutual benefits. For business history, it will apparently be expressed, in the first place, in an expansion of the spheres in which quantitative analysis is applied.

In particular, one promising line could be a comparison of AQFC in various industries and the history of development of large enterprises within these. Chandler (without using any kind of formulas or charts, for which he seems to have no special liking) has already demonstrated the effectiveness of such an approach for one concrete case, namely, in his subtle analysis of the activity of industrial conglomerates. This organizational form of enterprise, so fashionable in the 1960s, has turned out to be viable only in industries in which«capital costs are relatively low, specific skills not complex, synergies from R&D, production and distribution are limited» . 7 That is, where quasi-fixed costs are low and, consequently, there is no need for a large output of similar-type products over which to spread these costs.

An analysis of the limits of possible enlargement of enterprises (assessment of k ch ) is also very much in the spirit of Chandlerian business history. No wonder that instead of the more popular term minimum efficient scale Chandler makes use of the somewhat different concept of optimal plant size . The main specific feature of the latter is that it is not only oriented towards the technological characteristics of production, but also takes account of the size of the market. 8

The benefit for economic theory consists in a more realistic description of large enterprises, notably:

* in a closer consideration of their strong aspects, namely, their competitive advantages arising from the lowering of average quasi-fixed costs. In this way, an assessment of the role of large enterprises in the modern economy should become more positive. This also helps to resolve the long-standing paradox of the minimum efficient scale of enterprise: in almost every case, calculations suggest that actually operating firms are unjustifiably larger as compared with that scale. Could it be that, like the Soviet Gosplan , the spontaneous forces of the market keep spawning enterprises which are much too large for their own good? Evidently, the case is a much simpler one: the above-mentioned calculations simply fail to take into account the reduction in average quasi-fixed costs;

* in the possibility of explaining, by means of the Chandlerian economy of scale , the existence of large enterprises in industries where thetraditional economy of scale is insignificant, as, for example, in the pharmaceutical industry, in which the scale of production is small when reckoned in technological terms—no more than a few tons of effective substance now and again satisfy the requirements in medicines of the whole population of the world;

* in a better understanding of the interconnection between technical progress and the spread of large enterprises. As an exception, a great invention may be made without any expenditures at all, but systematic technical progress is inconceivable without vast outlays, mostly having the character of quasi-fixed costs. That is exactly why our age—an age of technical progress—is simultaneously an age of large enterprises. They alone are capable of reducing this type of costs per product unit down to proportions which are reasonable from the standpoint of the society;

* in a broader view of the problem of natural monopolies. Is the field of their spread largely limited to the infrastructural industries? Or do the competitive advantages of other large enterprises making active use of the Chandlerian economy of scale have a similar nature? In any case, the author of this article discerns very many common elements between a power company in possession of an electric wire network covering the whole city and an industrial giant with a marketing network sprawling across the entire world.

Let me end by making a suggestion concerning terminology. Would it not be better to replace the present term quasi-fixed costs , based as it is on purely formal grounds, with the term long-run fixed costs as a more apt reflection of this type of costs in the economic mechanism by means of which a company functions?

NOTES

1 Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., Scale and Scope. The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1990).

2 Ibid., p. 35

3 Ibid., p. 24, see also: Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., The Visible Hand. The Managerial Revolution in American Business (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1977), p.p. 281-283.

4 Cliff Pratten, The Importance of Giant Companies, (Lloyds Bank Review, Vol. 159, January 1986), p. 40

5 Zafer Achi, Andrew Doman, Olivier Sibony, Jayant Sinha, Stephan Witt, The Paradox of Fast Growth Tigers, (McKinsey Quarterly, #3, 1995), p.p. 9, 13.

6 Hal R. Varian, Intermediate Microeconomics. A Modern Approach. Fourth Edition (New York — London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996), p. 344.

7 Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., The Functions of the HQ Unit in the Multibusiness Firm (Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 12, 1991) p. 47.

8 Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., Scale and Scope. p. 27.